A few year ago, I attended a couple of talks by Dr. George Yancy, a philosopher at Emory University who, as one of the very few Black philosophers in this country, studies and thinks about race and whiteness. Though I have always considered myself to be anti-racist and ally to people of color, these talks dramatically changed how I think of myself and my role in racism.

In these talks, Dr. Yancy asserted the controversial notion that all White people in America are racist. He went on to explain that being White in America means not only absorbing all the implicit and explicit racist messaging surrounding us on a daily basis, but that we have benefited from that racism, whether we recognize it or not. This means, he noted, that the best a White person can be is an anti-racist racist. He drew a comparison with sexism, saying that as a man in America, the best he can be is an anti-sexist sexist.

These talks dramatically impacted the way I see my role in fighting racism in America. I had already decided to ensure I openly talked against racism in my professional and private life. But this perspective changed how I situated myself in this work and in these conversations, and furthered my dedication to not only confront my own racism, but that of others as well.

In justice and equity work, self-reflection is a critical and ongoing step in recognizing one’s privilege or marginalization, power or disempowerment, and responsibility to the community. As a White, cis-gendered woman, I began to think more deeply about my privilege as well as the ways I have been enculturated into White supremacy and racism. Once admitting this to myself (and others), I could begin to more purposefully and fully engage in strategies to counteract this particularly insidious form of socialization.

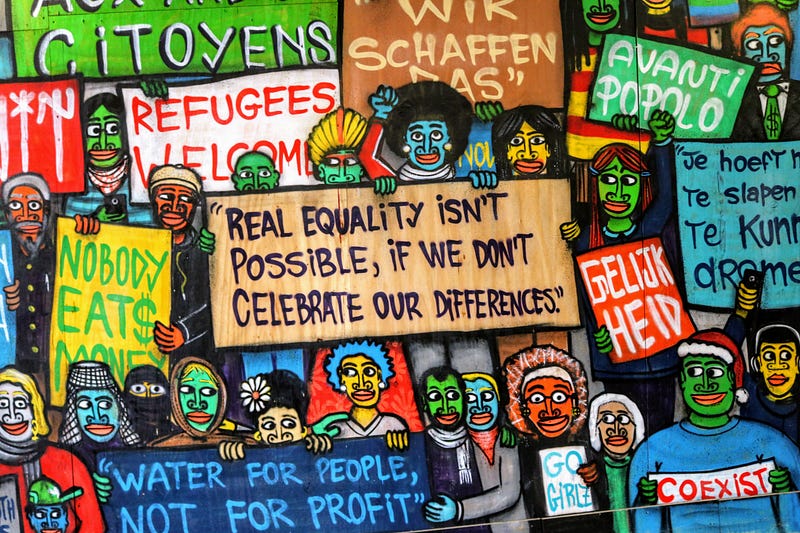

Over the years, I have realized there are several critical features to being an anti-racist racist.

1. Recognizing our racism: No one…and I mean no one…escapes the racist messages embedded in our society. It’s everywhere — TV, film, books, the news, our education system, etc. Further, if you are White, you have been more easily accepted in most cultural spaces than people of color. This acceptance is a huge step up. We must explore our privilege and our racist conditioning and how it emerges in our daily lives and thoughts.

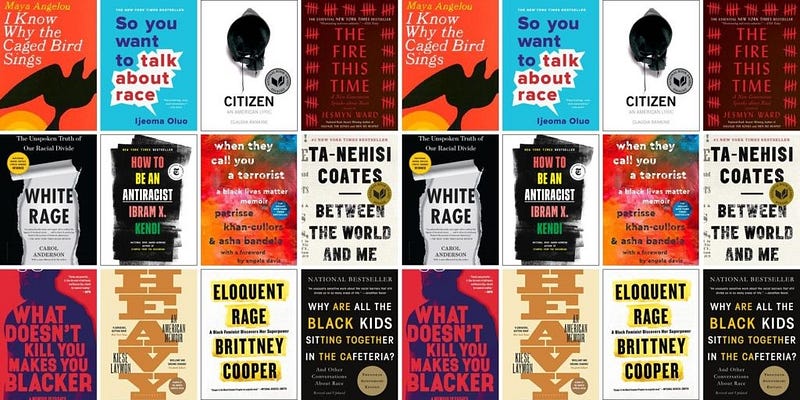

2. Humanize the ‘other’: When we are not exposed to people of difference, we typically hold one dimensional ideas of the ‘other’. Counteracting this notion is critical to becoming an anti-racist racist. Read, watch, listen to, and consume media and material made by people of color. Actively engage with this material to gain a sense of the complex lived experience of black and brown communities and individuals. [side note: it is not the responsibility of your friends, colleagues, and neighbors of color to teach you this information — we have vast information we can easily access for our own self-education]

3. Recognize our limited understanding: If you are white, no amount of reading or research will allow you to fully understand experience of being a person of color in America. Understand this limitation. You will never be the expert on the experience of racism in our communities. The best we can be is informed and willing to engage in lifelong learning.

4. Understand we are responsible for racism, and for its destruction: People of color are the victims of racism. White people are the perpetrators. It is our responsibility to fight racism and spread inclusion throughout our communities.

5. Speak up and speak out: We need to act to counteract racism. Otherwise these other steps are all for naught — the self-education and the self-reflection stays in the self, where it is helping no one. Actively fight racial injustice when and where you can. Be, as Dr. Bettina Love describes, a co-conspirator.

I want to be clear, admitting our racism and actively and constantly addressing racism in our communities is not easy. Neither is it a task to be weighed down by guilt. Guilt will only slow you down. Guilt will shifts the focus and attention away from those impacted by racism, to you who has benefited from it. Accepting that we have been raised in a White supremacist society and absorbed those messages is only helpful if you dedicate yourself to fighting the perpetuation of these messages and the consequence racist acts in our society.

I know I am an anti-racist racist. Only when I admitted this to myself was I able to effectively dedicate myself to eradicating racism in our country. Recognizing the part I play makes racism personal to me.

I am an anti-racist racist. Are you?

Books, Websites, Podcasts, Films to get you started:

We need to talk about injustice by Bryan Stevenson

The Urgency of Intersectionality by Kimberle Crenshaw

Ibram X. Kendi on How to Be Anti-Racist at UC Berkely

The Canary Effect by Robin Davey & Yellow Thunder Woman

A Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgment by Native Governance Center

…..Add your own in the comments!!