Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

-Article 22 of the UDHR

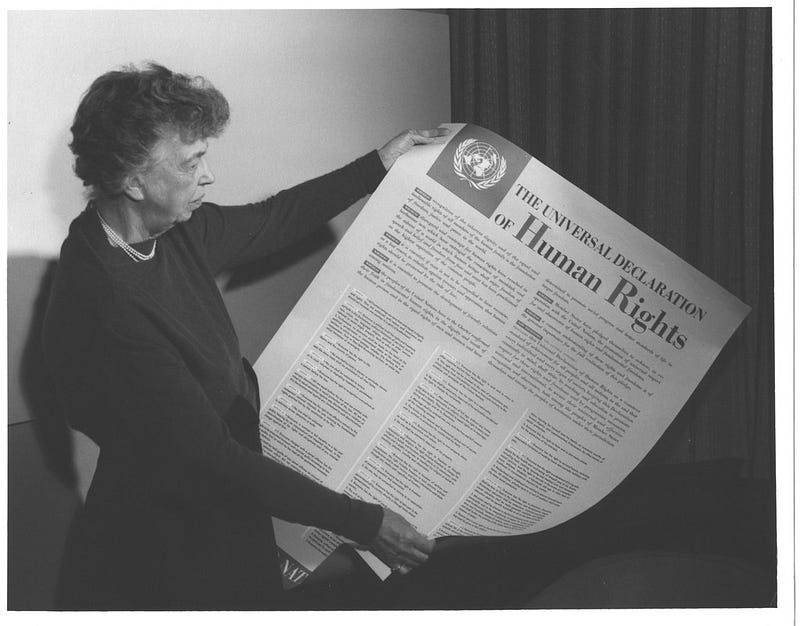

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was developed by a collection of world leaders, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, in 1948. This document set out ideals for an equitable, kind, humane world. Developed on the heels of WWII and the Nuremberg Trials, it was, and is, a greatly needed document. Since, then, the goals of the document have lessened in scope and power.

When I taught human rights at Emory University, my students would regularly feel frustrated by the limitations of modern-day human rights rhetoric and application. They (rightly) felt there was limited accountability for implementation and that even when nation work to meet basic human rights, it still seemed to fall short of truly lifting people up.

As I shifted my career into diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB), I began to see some important overlaps between human rights and DEIB. Specifically, I wonder if good diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging work is in the spirit of some of the most aspirational goals of the UDHR — equality, through equity.

A brief overview of the UDHR

The UDHR has 30 articles outlining human rights and freedoms. Though there is some criticism of the universality of the document, it is generally considered groundbreaking as a document that aimed to apply to all people, regardless of nationality, religion, ethnicity, age, gender, race, political ideology and more. The rights and freedoms include what are called negative rights (or rights of non-interference) such as the right to practice one’s religion, to peaceful assembly, to privacy, to marriage, to seek asylum, etc. There are also positive rights (or rights requiring action or resource support), such as the right to education, the right to work, and the right to health and well-being.

The positive rights are ones that most directly help ensure a person’s economic and social rights. Otherwise known as social rights, these are the rights that are most often ignored or sidelined throughout the world. Most assume these rights are ignored in the Global South, which is characterized a too poor to provide these resources. But the trend of denying these rights was actually led by the Global North, including the US; countries that were increasingly being driven by capitalism and neoliberalism.

As Samuel Moyn describes in Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World, when the UDHR was created, socialism was waning but not entirely gone. There was a push, particularly in nations emerging from colonialism, to create states in which everyone had equal access to goods. While new nations developed constitutions that included some basic provisions, it was not entirely mirrored in developed nations. As the rich became richer, capitalism rose globally, and socialism was roundly vilified. The consequences were that social rights fell by the wayside.

Along the way, an emphasis on sufficiency replaced equality for human rights. Nations and governments started defining the fullfilment of human rights as having ‘enough’ to live on and get by. What was ‘sufficient’ for survival, not what would create an equal distribution of goods, services, and rights. Not equity.

“The idea of belonging shouldn’t be considered a privilege available only to some. It should be considered a basic human right.”

- Linda Mullen, Executive Director of the Sparkle Effect, as quoted in Rhodes Perry’s Belonging at Work

With the rise of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) initiatives, it’s possible that the original aims of equality may be elevated even in our modern neoliberal, capitalistic environment.

The Role of DEIB

With a focus on ensuring people have the resources needed to thrive in their work life, DEIB is working towards fulfillment of the social rights noted above — more economic resources and social resources to participate in society and have one’s voices heard.

“By including social and economic rights in the struggle for human rights, we help to protect those most likely to suffer the insults of structural violence.”

- Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power

In other words, by ensuring peoples social rights, they can better enact all their human rights, including political and civic rights, and feel a sense of belonging in their communities. How can people work to improve their community if constantly distracted by ongoing poverty or exhausting workloads?

DEIB efforts — at least those that are done thoroughly and with a commitment to widespread change — center on creating mutual respect by increasing our understanding and appreciation of human difference and diversity. While most efforts are focused on the private industries, we do see similar moves in government, institutes of education, and community spaces (including human rights organizations themselves!).

And the proof of concept is there. Companies with good DEIB strategies have better employee retention. While this outcome is traditionally used to demonstrate the organizational benefits of DEIB, it is also good for individuals. Employees that feel safe, comfortable, and supported at work are not distracted by workplace stress and are less likely to desire to find a better work environment. When we aren’t distracted by negative experiences in our workplaces, we can be better, more involved citizens and humans.

So, could the growing DEIB movement be the bridge between the quasi-socialist ideals of the UDHR and the current neoliberal capitalist ideology? And in doing so, could it be a way to demonstrate that equity and equality improve upon our contemporary social ideals and aims?

I don’t want to suggest DEIB as a strategy to perpetuate capitalism, but just in a ‘nicer’ way. That is how some DEIB work is being done now — as a response to cultural trends that are all talk and no action and aimed only at company bottom lines. However, if DEIB has staying power and if it is increasingly done well — meaning it is integrated into mission statements, policies, onboarding, human resources, SOPs, etc and is seen as an ongoing process — perhaps there is hope that our local and global community will start to reevaluate the sufficiency versus equality divide. Maybe we will recognize the widespread benefits of making sure everyone thrives, instead of just survives. And possibly good DEIB work could contribute to a reduction of social and wealth disparities and all the social ills we are seeing as a result of the increasing divide.

Call me an idealist, but I think it has the potential.