tl;dr: Independence is a myth. Interdepedence is what defines us. Taking care of others is taking care of ourselves. Mask up. Get vaccinated.

I started studying disability studies and theories in 2008 when I began my doctoral program. Prior to this, I had never really engaged with critical theory and the work coming out of disability studies and from disabled thinkers. As someone who did not identify as disabled, what I was learning from these scholars gave words to much of the disquiet I experienced as a special educator. This field helped me understand why I felt unease employing behaviorism with autistic children, confusion over why we had to change behaviors that seemed to comfort the kids I worked with, and, most importantly, helped me think through the problems I saw in how our society treats disabled community members and each other.

As the pandemic proceeded, my knowledge of disability and feminist perspectives became critical to contextualize the public response to the pandemic. I thought specifically of the work examining individualism and independence, two American ideals that seem to form the foundation of our society. Exhausted with people refusing to get vaccinated and mask up, I tweeted about this back in August. With Omicron tearing through the world, I feel the need to revisit and reemphasize this perspective.

First, let’s talk about independence. Throughout the Global North, particularly in America, we are taught that we can do anything we want as long as we put our minds to it. We encourage people to ‘pull themselves up by their bootstraps’, ‘stand on your own two feet’, and idolize ‘rags to riches’ stories. It is the American dream after all.

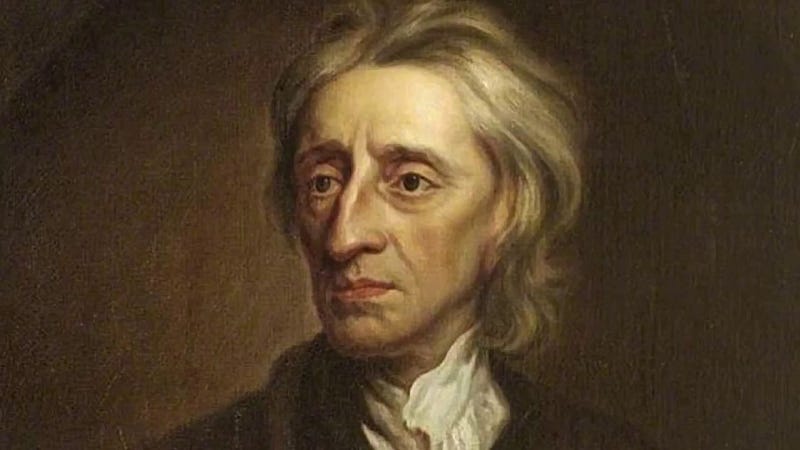

This dream is instituted into the very foundations of modern democratic society. It was expounded and perpetuated by early liberal philosophers. John Locke, whose work inspired the American revolution, emphasized individualism as well as property ownership and religious freedom. Utilitarian idol John Stuart Mill wrote about the importance of individual happiness, the calculation of which means some people’s happiness is forgone. Inspired by these and other Enlightenment thinkers, Thomas Jefferson centered individual ‘inalienable rights’ in the Declaration of Independence, where he wrote that ‘all men are created equal’ and have the right to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’.

It’s important to recognize that this early work came from a specific perspective — that of the white, cisgendered, land-owning man. These men had wives and mothers who cooked their food, cleaned and mended their clothes, and raised their children. What these men failed to realize was that their experience of independence actually relied on a lot of support. And, of course, these rights were developed with them and their peers in mind — they didn’t exactly apply to women, people of color, children, or people with disabilities.

Some of this early work on liberalism, individualism, and independence reflect modern values that should continue to be valued: freedom of religion, free speech, the basic right to live one’s life as one wishes. But the ideal of independence has grown into an imperative — if you are not independent, then you are not a good citizen, you are not a good person. Dependency has become a bad word.

And so now, we have people who are refusing the get a vaccine or wear a mask because of their natural right to independence and liberty. People who prioritize themselves and their circle over the good of the community. Who consider their individual interests as of equal import to the interests of society. Where has this independence as gotten us? As of the time of writing, it has contributed to the death of over 800,000 Americans and nearly 5 ½ million people worldwide.

But independence is a myth; it is, in fact, a dream. Unattainable. In reality, our actions and perspectives impact others. None of us exist in a silo. We rely on loved ones for emotional and material support. We rely on doctors for healing. We rely on farmers for food. We rely on religious leaders for guidance. We rely on teachers for knowledge.

In short, no one could get through a day entirely independently.

Some may argue that this is an exaggeration. That, sure, we all have our place in society and provide certain goods and services for communities, but there is a point at which we become responsible for ourselves and our futures. But this imaginary line in the sand is nebulous and ill-defined, even for those who believe in it. What level of dependency is too much? What is an acceptable level of dependency?

Disability and feminist scholars and thinkers emphasize the fact that no one is fully independent; we are all interdependent. While we may have different needs and rely on others to various extents, no one escapes interdepedence entirely.

In other words, interdepedence is a unifying feature of humanity itself. And so the myth of independence and the equation of dependence with weakness and even immorality — which drives ableism, sexism, elitism, and more — is at it’s core inaccurate. One could say it’s fake news.

What would happen if we embraced and celebrated interdependence and dependence? What would happen if we were taught the value interdependence rather than independence from birth?

I’m not arguing necessarily for collectivism—for transforming our identities into ones that are inseparable from that of the community (though I’m also not necessarily opposed to it). But I believe that we can hold both the idea that we can be our own people and that we need to care for our community as we care for ourselves. That we recognize and appreciate that we exist and survive because we live with and beside other humans, not in spite of them.

As we watch Omicron sweep the world and disrupt our lives — forcing students out of schools, hospitals to cope with overcrowding, travel to be disrupted, and visits to vulnerable family members halted — we should think about how much we truly value the illusion of independence. And ask ourselves why it is an illusion we hold on to so tightly, when in fact, our strength is in our dependency.

For more on the myth of independence, explore the works of Eva Kittay, David Mitchell, Sharon Snyder, Mia Mingus, Nirmala Erevelles, Sarah Ahmed, Martha Fineman, and Gayle Binion.

Readers: Feel free to also add other scholars or specific readings in the comments.